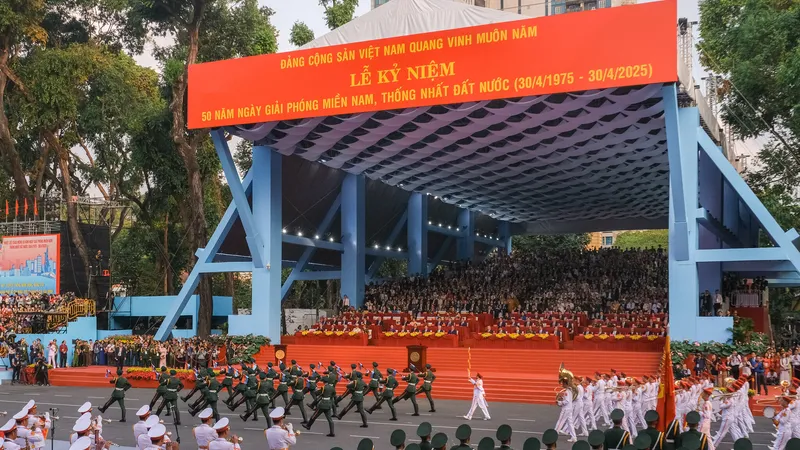

Ho Chi Minh City woke to a sea of red and yellow flags on April 30, 2025, as thousands poured into the streets to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon. The event, officially dubbed the Liberation of the South and National Reunification, wasn’t just a parade—it was a full-throated display of Vietnam’s pride, muscle, and memory. Soldiers in crisp uniforms marched shoulder-to-shoulder down Le Duan Street, a wide boulevard that cuts through the heart of the city, leading straight to the Independence Palace. Behind them, dancers twirled in traditional costumes, their movements sharp against the morning haze.

The parade was a beast—13,000 people strong, from grizzled veterans to young civilians waving banners. Russian-made fighter jets roared overhead, slicing through the sky in a rare air show that had kids craning their necks and old-timers nodding with approval. Helicopters thumped above, their blades chopping the humid air. On the ground, the crowd sang patriotic songs, their voices rising over the clatter of military boots. It was a moment that felt both scripted and alive, like the city itself was shouting its history.

This wasn’t just a party. The government had been planning this for months, with rehearsals kicking off as early as April 19. Thirty-eight armed units—army, navy, air force—had practiced their steps, their formations tight as a drum. The parade wasn’t just Vietnam’s show, either. China’s People’s Liberation Army joined in, alongside troops from Laos and Cambodia, a nod to regional unity that carried weight in a world watching closely. The message was clear: Vietnam’s past shapes its present, and it’s not standing alone.

Ho Chi Minh City, still called Saigon by some, has changed since April 30, 1975. Back then, tanks rolled through these streets as the Vietnam War—known here as the American War—ended with the North’s victory. Today, the city’s a buzzing metropolis of 9 million. Skyscrapers loom over the few crumbling buildings left from the war. Electric scooters zip past French colonial facades and American fast-food joints. Young people snap selfies in front of luxury stores, their lives a world away from the conflict that shaped their parents’ generation. Yet the parade brought it all back, tying the shiny present to the gritty past.

The speeches were fiery. Vietnam’s communist leaders called the 1975 victory “a triumph of justice,” a phrase that echoed through the crowd. Performers reenacted scenes from the war’s final days—soldiers storming the palace, the old regime crumbling. It was theater, sure, but it hit hard for those who lived it. Veterans in faded uniforms stood tall, their faces lined but eyes bright. For them, this wasn’t history—it was yesterday.

The parade stretched for hours, spilling across the city. Le Duan Street, lined with old trees and new billboards, became a river of people. Organizers had closed roads, rerouted traffic, and set up barriers to keep the chaos in check. By midday, the air was thick with heat and the smell of street food from nearby vendors. Families waved flags, kids perched on shoulders, and the songs kept coming—anthems of unity, of victory, of a country that’s still here, still standing.

On April 16, the government had announced the parade’s scale, promising a spectacle to mark the milestone. They delivered. The event was a blend of military precision and raw emotion, a reminder that Vietnam’s story is one of scars and swagger. The fall of Saigon wasn’t just an end—it was a beginning, and Ho Chi Minh City hasn’t forgotten.